Play isn’t a luxury. It’s foundational to healthy childhood development. An expanding body of interdisciplinary research confirms what many educators and parents instinctively know: unstructured, child-led play builds critical capacities across the physical, cognitive, emotional, and social domains.

Over the past 25 years, thousands of studies have explored play’s impact on executive function, self-regulation, emotional intelligence, cognition, creativity, and physical development. The findings are striking and consistent.

A Strong Start: Physical and Cognitive Development

We easily recognize play’s role in motor development. Whether climbing, building, or balancing, children strengthen both fine and gross motor skills through movement-rich environments.

But play also builds the brain. A growing body of research shows that executive functions like working memory, cognitive flexibility, and impulse control all develop through playful activity. Problem-solving, creativity, planning, and symbolic thinking are nurtured most effectively through hands-on, open-ended engagement.

One key study, a 2025 systematic review in the Journal of Intelligence, analyzed 25 empirical studies and found that loose parts play (LPP), involving open-ended materials, significantly enhances problem-solving, divergent thinking, and academic readiness.

In addition, a 2024 Frontiers review confirms that physical play is a key contributor to early motor coordination, and pretend play in particular allows children to explore consequences, integrate new learning, and simulate real-life scenarios. It also found both structured and unstructured play in preschool significantly improved motor and cognitive skills, especially when programs exceeded 3,000 minutes.

The Brain at Play

For a closer look at the brain’s inner workings, researchers often turn to animal models. A 2018 Science Direct study on juvenile rats showed that social play is essential for the development of inhibitory synapses in the medial prefrontal cortex, which is key to decision-making and impulse control. Rats deprived of social play displayed lasting deficits in cognitive flexibility, underscoring the necessity of early, unstructured interaction.

These findings are echoed in human studies. A longitudinal Australian study (Science Direct, 2022) followed children from ages 2 to 7 and found that 1–5 hours of active, unstructured play per day predicted significantly stronger self-regulation, regardless of earlier cognitive baselines.

Intrinsic Motivation and Lifelong Learning

Beyond cognitive and social development, play fosters something deeper: intrinsic motivation. Children engage in play for its own sake, for the joy of discovery, mastery, and expression; not for external rewards. This kind of internal drive is key to lifelong learning.

Research backs this up. The longitudinal study Free Play Predicts Self-Regulation Years Later shows a clear link between free play and long-term autonomy and creative thinking. The Encyclopedia of Early Childhood Development (2023) similarly confirms that exploratory play environments nurture imagination, independence, and a love of learning.

Mental Health and Emotional Resilience

Among the most compelling and often overlooked benefits of play are those related to mental health. Play helps regulate stress, boosts resilience, and protects against anxiety and depression.

The American Academy of Pediatrics’ 2018 policy statement The Power of Play recommends that pediatricians advocate for play just as they would for sleep and nutrition. Imaginative and physical play, they argue, reduce toxic stress and foster emotional well-being.

A 2020 study (National Library of Medicine) reinforced this, showing measurable increases in children’s reported happiness and playfulness following play-based interventions.

The Bottom Line for Educators and Policymakers

When it comes to shaping curriculum, pedagogy, and policy, the research is clear. Play is essential. It’s the work of childhood and the foundation of executive function, creativity, social well-being, and emotional resilience. Reducing or marginalizing playtime in the name of “academic focus” not only contradicts research, it undermines the very capacities children need to succeed in school and life.

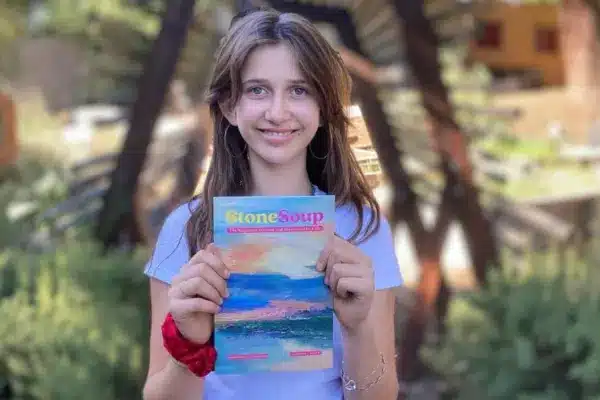

Waldorf education has long placed play at the heart of early learning. By integrating imaginative play, rich sensory experiences, and unstructured exploration, Waldorf schools offer children the developmental foundation they need to grow into capable, resilient, and joyful learners.

By investing in environments, practices, and policies that prioritize play, we invest not only in children, but in healthier, more capable, and more adaptable adults.

Photo Credit: The Waldorf School of Philadelphia